Geometry of Fear: Decoding the Composition of The Great He-Goat

- Jan 18

- 3 min read

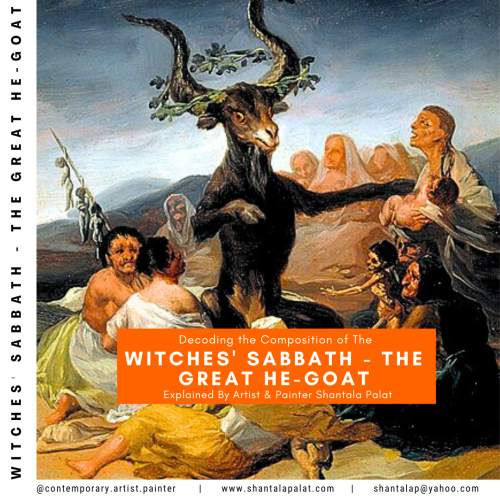

Francisco Goya’s The Great He-Goat is not merely a disturbing image from his Black Paintings series; it is a carefully constructed visual statement rooted in fear, power, and psychological tension. At first glance, the painting appears chaotic and ominous, but beneath its darkness lies a deliberate geometric structure that intensifies its emotional impact.

By decoding the composition of The Great He-Goat, we uncover how Goya used form, spatial arrangement, and visual balance to transform fear into a calculated artistic language, says Shantala Palat, who is a top contemporary Indian artist and painter.

Context Behind the Darkness

Painted between 1819 and 1823 on the walls of Goya’s home, The Great He-Goat reflects the artist’s disillusionment with society, superstition, and authority. The central figure, often associated with Satan or a pagan deity, presides over a gathering of shadowy figures. While the subject matter is unsettling, it is the composition that gives the painting its enduring psychological power. Goya was no longer interested in classical harmony; instead, he reshaped geometry to serve fear.

The Central Axis of Power

The composition is anchored by the he-goat itself, positioned slightly off-center yet dominating the visual field. Its dark mass forms a strong vertical axis, immediately commanding attention. This placement is intentional. Rather than situating the figure symmetrically, Goya shifts it just enough to create imbalance, reinforcing unease. The goat becomes the gravitational core around which all other forms revolve, symbolizing control, dominance, and looming threat.

Circular Geometry and Ritualistic Space

One of the most striking compositional elements is the implied circular arrangement of the surrounding figures. The group forms a rough arc or semicircle that directs the viewer’s gaze inward toward the goat. This circular geometry evokes ritual, enclosure, and entrapment. There is no clear escape path for the eye; movement is guided repeatedly back to the central figure. The geometry mirrors the psychological experience of fear itself, cyclical and inescapable.

Use of Diagonals to Create Tension

Goya employs diagonal lines throughout the painting to disrupt stability. The slanted postures of the figures, the tilt of heads, and the uneven horizon all contribute to a sense of collapse. Diagonals are traditionally associated with motion and instability, and here they amplify emotional disturbance. The viewer feels as though the scene is perpetually on the verge of tipping into chaos.

Negative Space and the Weight of Darkness

Unlike classical compositions that balance positive and negative space harmoniously, The Great He-Goat uses darkness as a structural element. Large areas of shadow compress the scene, closing it in. The background offers no relief, no depth of landscape, only an oppressive void. This manipulation of space flattens the composition, forcing figures forward and heightening claustrophobia. Fear, in this geometry, has mass and weight.

Distorted Proportions and Psychological Geometry

The figures surrounding the goat are rendered with exaggerated or distorted proportions. Faces appear elongated, bodies merge into shadow, and individuality dissolves. This distortion is not random; it disrupts recognizable human geometry. By breaking anatomical norms, Goya destabilises the viewer’s sense of reality. The composition suggests a world where natural order has collapsed, replaced by irrational belief and collective hysteria.

Light as a Geometric Tool

Sparse and uneven lighting plays a critical compositional role. Light does not illuminate evenly but instead fragments the scene. Select faces emerge briefly before being swallowed by darkness. This selective illumination creates visual rhythm, guiding the eye in short, uneasy movements rather than smooth transitions. Geometry here is fractured, reinforcing the theme of moral and psychological fragmentation.

The Great He-Goat is a masterclass in how composition can embody emotion. Goya’s use of asymmetry, circular arrangements, diagonals, and oppressive space transforms geometry into a language of fear. Rather than offering visual clarity or balance, the painting traps the viewer in a controlled disorder. By decoding its composition, we see that the terror of The Great He-Goat does not come only from its subject, but from the calculated way every line, shape, and shadow conspires to unsettle the human mind.

Comments